Ancient Life in Kansas Rocks, part 3 of 27

|

Will the footprints of astronauts on the moon be regarded as fossils someday? |

Fossils may be very large, as most persons know from pictures they have seen of large dinosaurs, or very, very small, detectable only through the study of rocks under electron microscopes. Fossil spores and pollen of plants millions of years old are commonly studied, as are minute sea organisms dating back to the dawn of life. These small fossils are not noticeable in the field, but can be seen only by examining the rocks with a microscope in the laboratory.

We think of fossils as being in rocks, or at least as being objects that are dug up, or unearthed. This is appropriate, for the word fossil means something dug up. They are also most commonly considered as part of the rock or earth from which they are extracted, and therefore are the same age, or as old as the rocks within which they are found. This is a very important point, because it is the idea that the fossils are of the same age as the rocks that contain them that makes fossils the valuable tools with which the geologist works. Why is this so? In simple terms, the animals and plants that existed at any one time in the history of the earth, have not existed before or since. Sometimes, unique forms of life existed over very short spans of time, and simply by finding one such unique form one may determine the age of the rock in which it is found. Most commonly, however, we find a number of different kinds of fossils which, taken all together, occurred at only one time, although the individuals may have existed with no observable change over longer spans of time.

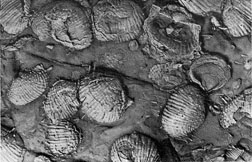

Brachiopods, small-shelled marine animals, were abundant in Kansas seas more than 250 million years ago. |

|

An example of the former method may be where a person was born and died within a year, and simply by seeing his name as being present, we know what year that was. An example of the latter method is where we see a list of a family gathering, with great grandmother and great grandchild, each of who lives to 100 years. We cannot pinpoint with accuracy the time of the gathering knowing only that the great grandmother lived, say from 1772 to 1872, or only that the great grandchild lived from 1871 to 1971, but taken together, we may pinpoint the time of the gathering at the years 1871-1872, the only time during which the lives overlapped. Thus, when we find several fossils in one place whose time spans of existence overlap, the group can tell us how old the enclosing rock must be. The geologist may find similar assemblages of fossils in rocks separated by considerable distances, even oceans, and thus be able to say that rocks from different localities in different states, or even on different continents, are of similar age. This is called correlating the age of the rocks.

As well as the age of the rocks, fossils may be used to tell us about the environments in which the organisms lived and thus in which the rocks were deposited. We observe organisms every day that live in certain areas and not in others, and we can readily understand that at any one time we will find different kinds of organisms that are typical of different environments. For example, the plants that grow in open meadows merge with different plants that grow on the woodland borders, and these in turn are different from those that grow deeper in the forests. Similarly, if one were to picture an ocean shoreline such as that of the Gulf of Mexico, there are certain organisms that live at considerable depths far offshore, a somewhat different assemblage of organisms that live near the shore, another on the shore between high and low tide lines, another well up on the beach or sand bar, another in the shallow lagoon that may be present behind the sand bar, and so on. By studying the rock and the assemblage of fossils within it, it is commonly possible to describe the ancient environment. Importantly, and this is a difficult concept, we may be able to describe different environments that existed at the same time but in different areas. We shall not go into this here, except to mention that the Kansas rocks are very important in giving the geologist information about ancient shallow-sea environments by virtue of the plentiful and well-preserved fossils of different kinds easily found over much of the state.

|

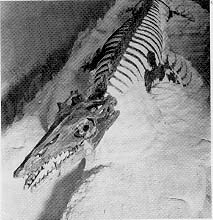

Platecarpus was a mosasaur, a very large marine lizard that flourished in the Upper Cretaceous seas. Note how the paddle-like limbs, ending with webbed feet, adapted this large reptile to a life of swimming in the deep sea. This specimen was one of the earliest collected by the Museum of Natural History at The University of Kansas and is now on display there. It was located in 1890 in Graham County, west of Hill City in the Niobrara Formation. |

On the following pages are illustrations and brief descriptions of many of the common fossils found in Kansas. No attempt has been made to use the most perfect of specimens, for they are not the most common. The fossils shown here, on the other hand, are typical of what one may expect to find on a casual outing.

Where may one find fossils in Kansas? Over much of the state, one must merely look at the ground to find them. Do not search on vegetated surfaces, but rather look where the rock is exposed, or nearly so. Look at rocks where the highway has been cut through, or along river banks or in fields where the rocks crop out. Commonly, the action of rain, frost, and wind etches the rock matrix away from the fossil and leaves it exposed in relief, or sometimes frees the fossil entirely so that it simply lies loose on the surface.

A note of caution. One should not carelessly gather fossils, separate them from the rocks, and then discard them. Fossils are important tools to the researcher and are of value to the serious collector. If you find specimens that you wish to collect, they should be wrapped and labeled. You should keep a notebook assigning a number to each specimen and describing with the greatest amount of accuracy the exact location from which the specimens are taken. A description of the rock strata should be included, referring to the rocks above and below, the thickness of the rock layer and its color, other fossils in the same rock, the date and so forth. The same specimen number should be written on the specimen in indelible ink. In this fashion, you will always have a record of the specimen, and this record can be passed on should you wish to trade or donate your find. The exact name of the fossil is not the most important, because the name may change as our knowledge increases, but the locality where it was found will not.

PHOTO HERE of FOSSIL HUNTERS?

Never remove or destroy fossils if you are not interested in them. If you feel that your find is particularly important, especially with regard to fossils of animals with bones or unusually large exposures of delicately preserved specimens, note the locality with precision and contact the nearest college or university natural history museum, or contact the Kansas Geological Survey. In this fashion, the specimen may be properly extracted for the greatest benefit to all. Never disturb remains or artifacts that you may suspect to be of human origin. (It may even be against the law!)

Whether you are on a picnic and discover a fossil, or are a student exploring the curiosities of nature, or are just having some fun in the field trying to find fossils, it is hoped that the following pages will help you gain an idea of what to look for, or what it is that you have found.

Photo of lunar footprint courtesy of Marshall Space Flight Center.

Kansas Geological Survey

Placed online Feb. 1997

URL = "http://www.kgs.ku.edu/Publications/ancient/rep03.html"

Send comments and/or suggestions to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu